It is now over seventy years since Schwitters’ Merzbau was destroyed during an RAF bombing raid on the city of Hannover. Schwitters’ himself only learned of its destruction some eighteen months later. What follows is a description of that raid, pieced together from documents in the archives of the Royal Air Force, Hendon and at the National Archives in Kew.

It was not an exceptional raid and like most of similar raids against German towns and cities, designed less to inflict economic damage and reduce Germany’s ability to prolong the war, but rather to demoralize German civilians. RAF Operation Order 91, simply instructed Squadron 226 to “cause maximum damage at the aiming point at Hannover”[1]. In present day language the unfortunate destruction of 5 Waldhausenstrasse, the Schwitters’ family residence, was simply collateral damage. For Schwitters’ the loss of what he regarded as his most important artistic work, must have been devastating, not least because one reason for his wife Helma remaining in Hannover, when he went into Norwegian exile, was to ensure that the property and with it the Merzbau, was kept out of the hands of the National Socialist regime. Now he learned that not only was his wife dead from cancer but that the Merzbau itself was no more. [caption id="attachment_8" align="alignright" width="300"] One of the Lancaster bombers that took part in the Hannover raid of October 1943 survived the war and is now on display at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London.[/caption]

On the night of 8-9th October 1943 five hundred and four RAF aircraft visited Hannover, fuelled with eight thousands litres of petrol and with bomb bays crammed with five tons of bombs and incendiaries. From their bases in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire it took the aircraft a little over three and a half hours to reach the city, which previously had been relatively lucky, earlier raids often having had difficulty locating the target, and bombs had been dropped mostly on the outskirts and in the fields to the west and north of the city. The first aircraft took off just after five and by eight thirty were over the target. The successive waves of bombers had cover from fighter escorts from the English coast to just west of Osnabruck but after that point, on their final one hundred and fifty kilometers to the target, they were unprotected. Various flight plans had been suggested for attacking Hannover but finally, according to one tactical plan for attacking Hannover, “a direct route from the Leeuwarden area directly to Hannover and back is considered most advantageous since it exposes the main bomber force to enemy action for the shortest possible time”[2]. The shortest route also reduced the amount of fuel to be carried and allowed for a heavier bomb-load. On that night the markers dropped by the pathfinders overshot the city centre by a couple of miles but over the next six hours of bombing the aim of successive bombers gradually crept back over the city centre. The final wave of bombers had not taken off when the earliest aircraft to bomb the city had already returned. From the immediate de-briefing reports of the first returning crews, it could be supposed that the attack was proving as ineffectual as previous raids on the city. Lancaster DV188 reported that the “attack appears very poor taking into account the number of aircraft employed”[3]. Even some later aircraft reported, “Fires started by the first four waves seemed very few for the number of aircraft taking part”[4]. Pilot Officer Heap, whose aircraft bombed the city from the remarkably low level of thirteen thousand feet, called the raid, “a wasted effort[5]”. But as the night wore on reports from the bombers reflected with greater accuracy what was happening on the ground. Lancaster DV274, bombing from twenty thousand feet at 0137 reported “fires burning well[6]” and Pilot Officer Drane in Lancaster EE173 described, “Quite a good prang”. Worries about fighter attacks proved exaggerated as for once the decoy raid on Bremen was successful in distracting the air defence fighters of the Luftwaffe and out of the five hundred and five aircraft taking part in the raid, few reported any real problems from fighters. Of the twenty-seven aircraft lost most were brought down by flak though night fighters shot down a few after leaving the air space over the city. Lancaster JA980 was well clear of the city when it was attacked at eighteen thousand feet and crashed some forty kilometers southwest of Hannover near the town of Rinteln. Other aircraft came down near Stadthagen, Barsinghausen and Petershagen. Over the target Lancaster JB174 of 97 Squadron suffered a direct hit from flak, which took off the nose of the plane and only the pilot managed to escape by parachute.

[caption id="attachment_9" align="alignright" width="236"]

One of the Lancaster bombers that took part in the Hannover raid of October 1943 survived the war and is now on display at the RAF Museum, Hendon, London.[/caption]

On the night of 8-9th October 1943 five hundred and four RAF aircraft visited Hannover, fuelled with eight thousands litres of petrol and with bomb bays crammed with five tons of bombs and incendiaries. From their bases in Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire it took the aircraft a little over three and a half hours to reach the city, which previously had been relatively lucky, earlier raids often having had difficulty locating the target, and bombs had been dropped mostly on the outskirts and in the fields to the west and north of the city. The first aircraft took off just after five and by eight thirty were over the target. The successive waves of bombers had cover from fighter escorts from the English coast to just west of Osnabruck but after that point, on their final one hundred and fifty kilometers to the target, they were unprotected. Various flight plans had been suggested for attacking Hannover but finally, according to one tactical plan for attacking Hannover, “a direct route from the Leeuwarden area directly to Hannover and back is considered most advantageous since it exposes the main bomber force to enemy action for the shortest possible time”[2]. The shortest route also reduced the amount of fuel to be carried and allowed for a heavier bomb-load. On that night the markers dropped by the pathfinders overshot the city centre by a couple of miles but over the next six hours of bombing the aim of successive bombers gradually crept back over the city centre. The final wave of bombers had not taken off when the earliest aircraft to bomb the city had already returned. From the immediate de-briefing reports of the first returning crews, it could be supposed that the attack was proving as ineffectual as previous raids on the city. Lancaster DV188 reported that the “attack appears very poor taking into account the number of aircraft employed”[3]. Even some later aircraft reported, “Fires started by the first four waves seemed very few for the number of aircraft taking part”[4]. Pilot Officer Heap, whose aircraft bombed the city from the remarkably low level of thirteen thousand feet, called the raid, “a wasted effort[5]”. But as the night wore on reports from the bombers reflected with greater accuracy what was happening on the ground. Lancaster DV274, bombing from twenty thousand feet at 0137 reported “fires burning well[6]” and Pilot Officer Drane in Lancaster EE173 described, “Quite a good prang”. Worries about fighter attacks proved exaggerated as for once the decoy raid on Bremen was successful in distracting the air defence fighters of the Luftwaffe and out of the five hundred and five aircraft taking part in the raid, few reported any real problems from fighters. Of the twenty-seven aircraft lost most were brought down by flak though night fighters shot down a few after leaving the air space over the city. Lancaster JA980 was well clear of the city when it was attacked at eighteen thousand feet and crashed some forty kilometers southwest of Hannover near the town of Rinteln. Other aircraft came down near Stadthagen, Barsinghausen and Petershagen. Over the target Lancaster JB174 of 97 Squadron suffered a direct hit from flak, which took off the nose of the plane and only the pilot managed to escape by parachute.

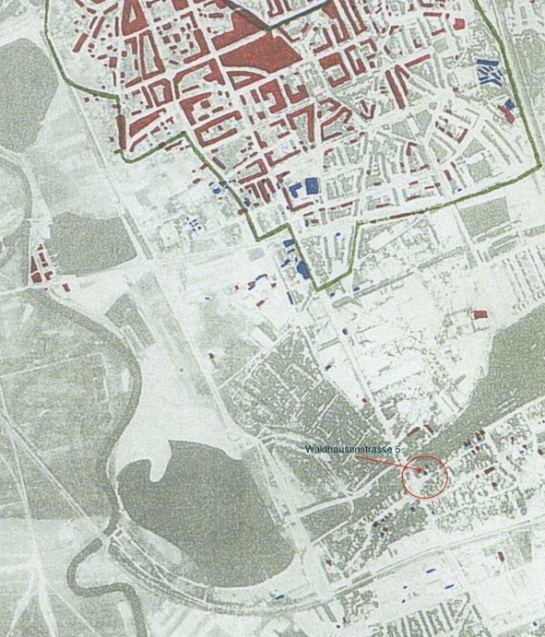

[caption id="attachment_9" align="alignright" width="236"] The site of the Sprengel Museum can be seen at the north-east tip of the Maschsee. Waldhausenstrasse lies just of the bottom-right-hand corner of this photograph.[/caption]

On the ground the city centre was now well alight. Most planes carried a four thousand pound bomb, which on detonation would shatter windows and strip roofing tiles from nearby buildings. The rest of the bomb-load was made up of incendiaries spreading fire through the roof spaces opened up by these heavier bombs. In the days following the raid reconnaissance aircraft secured almost a hundred percent photographic coverage of the city. The interpretation report based on these photographs commented that, “the fires seen raging and blanketing the town with smoke the day after the raid, have spread and devastated a large elliptical area measuring about a mile by two miles between the main station and the Maschsee. In their paths these fires have indiscriminately taken toll of shops, offices, churches, museums and often buildings of historic interest. In this fully built-up zone nearly fifty-four percent of the buildings have been totally destroyed”[7]. In five short lines the damage report lists the destruction of sixteen schools, eleven churches, seven hospitals, five theatres and four museums. Invisible from the air were the over one thousand two hundred killed, the three thousand three hundred and forty-five injured and the nearly eight thousand with serious eye injuries caused by the heat and the smoke. Had the Mosquito reconnaissance aircraft paid more attention to the northwestern suburb of Stöcken they could have seen the freshly turned soil marking the mass graves of these victims.

[caption id="attachment_17" align="aligncenter" width="545"]

The site of the Sprengel Museum can be seen at the north-east tip of the Maschsee. Waldhausenstrasse lies just of the bottom-right-hand corner of this photograph.[/caption]

On the ground the city centre was now well alight. Most planes carried a four thousand pound bomb, which on detonation would shatter windows and strip roofing tiles from nearby buildings. The rest of the bomb-load was made up of incendiaries spreading fire through the roof spaces opened up by these heavier bombs. In the days following the raid reconnaissance aircraft secured almost a hundred percent photographic coverage of the city. The interpretation report based on these photographs commented that, “the fires seen raging and blanketing the town with smoke the day after the raid, have spread and devastated a large elliptical area measuring about a mile by two miles between the main station and the Maschsee. In their paths these fires have indiscriminately taken toll of shops, offices, churches, museums and often buildings of historic interest. In this fully built-up zone nearly fifty-four percent of the buildings have been totally destroyed”[7]. In five short lines the damage report lists the destruction of sixteen schools, eleven churches, seven hospitals, five theatres and four museums. Invisible from the air were the over one thousand two hundred killed, the three thousand three hundred and forty-five injured and the nearly eight thousand with serious eye injuries caused by the heat and the smoke. Had the Mosquito reconnaissance aircraft paid more attention to the northwestern suburb of Stöcken they could have seen the freshly turned soil marking the mass graves of these victims.

[caption id="attachment_17" align="aligncenter" width="545"] RAF Damage Assessment Map produced from aerial photographs taken on 11th/12th October 1943. Identified bomb hits are marked with a red stop one of which can be seen on Waldhausenstrasse.[/caption]

The same report lists the extensive damage caused to Hannover’s manufacturing industry but most of this had been accidental. The Hanomag plant producing field guns and the Continental plant producing the tyres on which the Wehrmacht rolled over Europe, both lay to the north of the zone marked out by the pathfinders. At his Nuremburg interrogation in May 1945 Albert Speer noted the failure of the bombers, on this and later raids, to hit the Agfa accumulator factory and that “had this factory been destroyed the construction of U-boats would have had to be abandoned four weeks later”[8].

[caption id="attachment_23" align="aligncenter" width="300"]

RAF Damage Assessment Map produced from aerial photographs taken on 11th/12th October 1943. Identified bomb hits are marked with a red stop one of which can be seen on Waldhausenstrasse.[/caption]

The same report lists the extensive damage caused to Hannover’s manufacturing industry but most of this had been accidental. The Hanomag plant producing field guns and the Continental plant producing the tyres on which the Wehrmacht rolled over Europe, both lay to the north of the zone marked out by the pathfinders. At his Nuremburg interrogation in May 1945 Albert Speer noted the failure of the bombers, on this and later raids, to hit the Agfa accumulator factory and that “had this factory been destroyed the construction of U-boats would have had to be abandoned four weeks later”[8].

[caption id="attachment_23" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Post-war photograph of Waldhausenstrasse after Number 5 had been demolished.[/caption]

Post-war photograph of Waldhausenstrasse after Number 5 had been demolished.[/caption]

When I visited the Royal Air Force archive in North London an archivist unearthed the original damage assessment map produced just after the raid. In red pen it showed the location of damaged and destroyed buildings (see extract from this map above). The area around Kröpke (the heart of the city) was almost solid red. Red covered the streets around the ruined St Aegipius Kirche and far south of the main target area a single red dot showed where one stray bomb had destroyed the masterwork of arguably Hannover’s greatest artist, Kurt Schwitters. With an irony that Schwitters himself might have appreciated, he was one Hanoverian who was safe that night from the murderous torrent of bombs unleashed on his city as he slept soundly in his house in Westmoreland Avenue, Barnes, West London, an exile from Germany since 1937.

[caption id="attachment_10" align="aligncenter" width="300"] Clearing debris on Cellestrasse - October 1943[/caption]

Clearing debris on Cellestrasse - October 1943[/caption]

A few weeks earlier, on as grey and raw a November day as can be imagined, I had visited the vast cemetery in the suburb of Stöcken. Down it’s long lanes I walked, between the substantial confident memorials to Hannover’s worthy and long dead until finally, just as cold was urging a retreat, I dimly spotted the large cross standing dark between grey birches and then beyond the acres of short squat stones marking the graves of war dead. The sight is quite shocking. I counted barely two dozen names from that night though it was clear that most of the victims must lie anonymously in the mass grave occupying the central lawn. Still more bodies lie in the other cemeteries that surround the centre of the city including those of the RAF aircrew who never made it back to Oakington or Wickenby, Binbrook or Bourn; whose ticket to Hanover was clearly one-way and who now lie in the Commonwealth War Cemetery to the west of the city. A short distance from these civilian victims of the Second World War lie a thousand or more soldiers who died from wounds received on the battlefields of France. Through another glade lie almost one hundred victims of the German Revolution of January 1919, members of the Freikorps who thought it their patriotic duty to defend the Kaiser Reich from the democracy of Weimar or from socialism. And just beyond lies the body of a twenty-one year old militant who died in 1936 in uncertain circumstances but whose allegiance to the Nazi regime can be inferred from the eagle holding the swastika in its talons that adorns his grave.

[caption id="attachment_11" align="aligncenter" width="545"] Mass grave for victims of the bombing raids of October 1943 - Stocken Friedhof, Hannover[/caption]

Mass grave for victims of the bombing raids of October 1943 - Stocken Friedhof, Hannover[/caption]